The Ottoman Millet System and the Rise of Assyrian Nationalism

Pictured: Indigenous Assyrians working at a printing press at Ūrmī in present-day north-west Iran. From the collection at the Presbyterian Historical Society.

Under the Ottomans (c. 1515–1922), most Assyrians lived as subjects and their millennia-old cultural identity was heavily fragmented as a result of the empire’s millet system— from Arabic meaning “nation”. The millet system was the way in which the Ottomans administered non-Muslim religious communities— i.e., the millets —in the empire.

In fact, non-Muslims had to be part of a millet to be considered citizens of the empire. Thus, in 1829, the Syriac Catholic Church received the status of a separate millet, followed by the Chaldean Catholic Church in 1844, and the Syriac Orthodox Church in 1882.

The Church of the East petitioned for a millet status of its own in 1864. This initially failed, however, was later granted in 1914.

Pictured: This print comes from John Speed’s (1552–1629) well known 1626 map, The Turkish Empire. Represented here are Ottoman subjects in a series of ethnographic vignettes, one of which is described as “an Assyrian” and “his wife”.

On the one hand, by obtaining a millet status, Christian religious hierarchs were elevated to positions of power, prestige, and privilege. On the other hand, such policies encouraged societal divisions among the Assyrians and encouraged sectarian-based religious identities (i.e., Nasturi “Nestorian”, Süryani “Syriac”, and Keldani “Chaldean”) to flourish.

In some parts of the empire, the Assyrians were considered “tribal” and thus were semi-independent, providing their own administration, protection, and services, paying a nominal tribute to the Ottoman Government. This, however, was limited to the five tribes in the Hakkārī highlands, as well as the district of Rāyiṭē in Ṭūr ʿAbdīn.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the concept of nationalism as well as hopes for political independence took hold among various subject people in the Ottoman Empire. This included and was not limited to the Assyrians, Armenians, Arabs, Greeks, and Kurds.

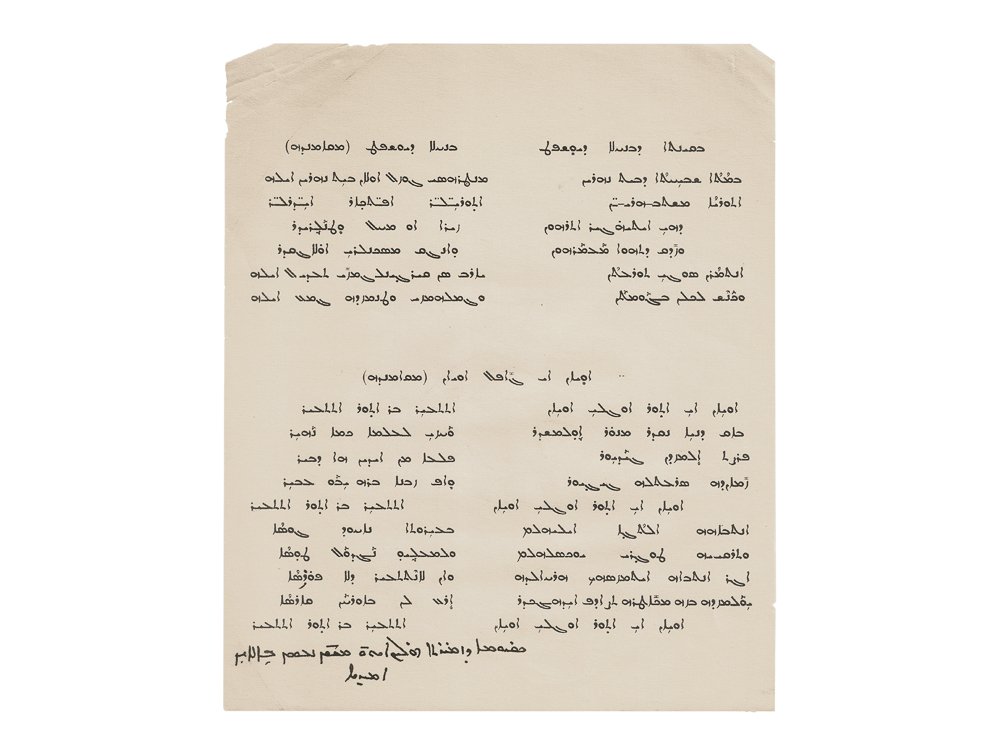

Pictured here is Naʿūm Fāʾiq’s (1868–1930) well-known 1910 poem titled Awake, Son of Assyria. An adherent of the Syriac Orthodox Church, Fāʾiq is considered to be one of the earliest pioneers of Assyrian nationalism. During his lifetime, Fāʾiq actively called for the reunification of the Assyrian people, irrespective of millet. In fact, he co-founded a civil organisation called ʿirūthā “Awakening” in the city of Āmīd as well as a number of periodicals: Kawkāb Madenḥā “Star of the East”, Ḥūyādā “Unity”, and Bēth-Nahrīn “Mesopotamia”.

Although the millet system was an institutional framework through which the Ottomans separated and governed their subjects; it did, however, have the unintended effect of paving the way for nationalistic ideologies to flourish. This, coupled with the establishment of the first printing presses among the Assyrians— the concept for self-determination was widely circulated and gained immense popularity.

In contrast to the divisive and sectarian-based identities perpetuated by the millet system, nationalism not only promised to offer the Assyrians political sovereignty but recognised their people as a single united ethnic and national group. Thus, the Assyrians— irrespective of their church affiliation —could conceive themselves as political equals and the heirs of a rich heritage, rather than Ottoman subjects or coreligionists of their respective sectarian groups.

It may also be argued that although nationalism drew inspiration from Western ideas— the Assyrians had maintained a nationalistic spirit of their own. In 1841, for instance, Horatio Southgate, an American missionary to the Ottoman Empire, observed that Armenians did not know Syriac Christians at Ḥarpūt (modern-day Elazığ Province, Türkiye) by the name he used “Syriani; but called them Assouri.”

Southgate was also astonished to find that the community identified itself as Assyrians, “being sons, as they say, of Assour, (Asshur,).”

-

The author of this article is indebted to Mr. Abboud Zeitoune for supplying the high-resolution image of Naʿūm Fāʾiq’s Awake, Son of Assyria poem.

-